July 16, 2025

The Story Behind the House That Became Dilworth Center

When development plans met a community’s resolve.

In the heart of Dilworth Charlotte, where tree-lined streets and front porch conversations still define the pace of life, a defining moment in the neighborhood’s modern history began—not with a grand development plan, but with a quiet house on Park Road.

That house still stands today. Not in its original spot, but still rooted in the community. It now serves as the home of Dilworth Center, a trusted presence in addiction treatment and recovery. But decades ago, it was the spark that lit a neighborhood movement.

The House That Nearly Vanished

A Community Draws the Line

Preservation Through Conflict

From Resistance to Renewal

A New Chapter: Weddings, Work, and Full Circles

A Name That Carries Weight

A House Finds Its Purpose—Again

Celebrating 35 Years of Purpose

Today, in 2025, Dilworth Center celebrates 35 years of helping those in the community. The building that once rallied a neighborhood to action has become a place where recovery begins, relationships are repaired, and futures are rebuilt.

For the thousands who have walked through its doors, 2240 Park Road is more than just an address—it’s a place of renewal and strength, where the hard work of recovery is met with support, structure, and dignity. And for those who have dedicated their careers to this mission—like Charles Odell (current CEO and President), Cori Trotman, Abier Thornton, and Christina Melber, who were here in Dilworth Center’s earliest days and remain committed today—it is a daily testament to the power of perseverance and purpose. The house has stood the test of time, and so have the people in it.

Some buildings get repurposed. Others become something more: living symbols of what a community can achieve when it chooses preservation, intention, and people over profit.

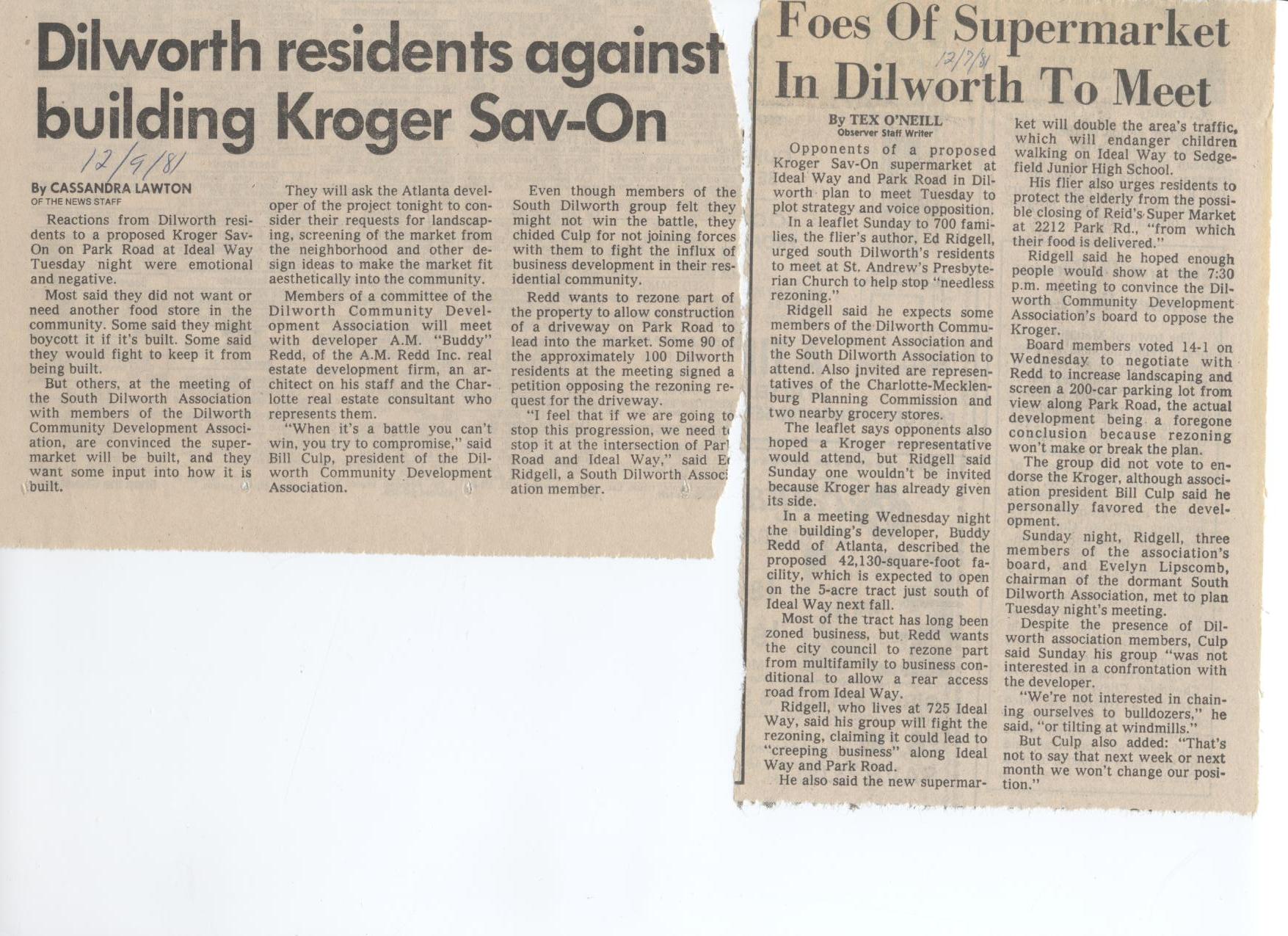

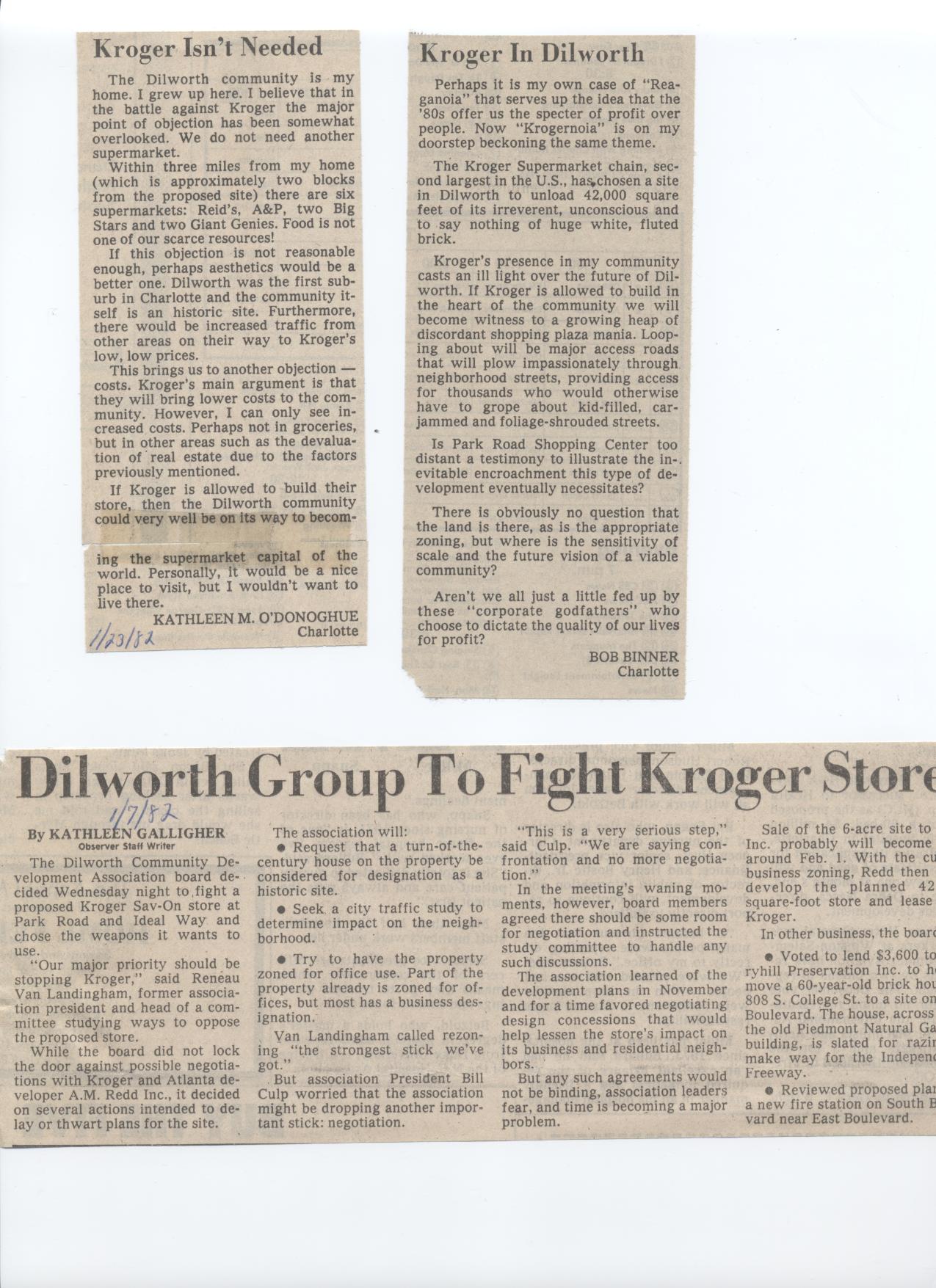

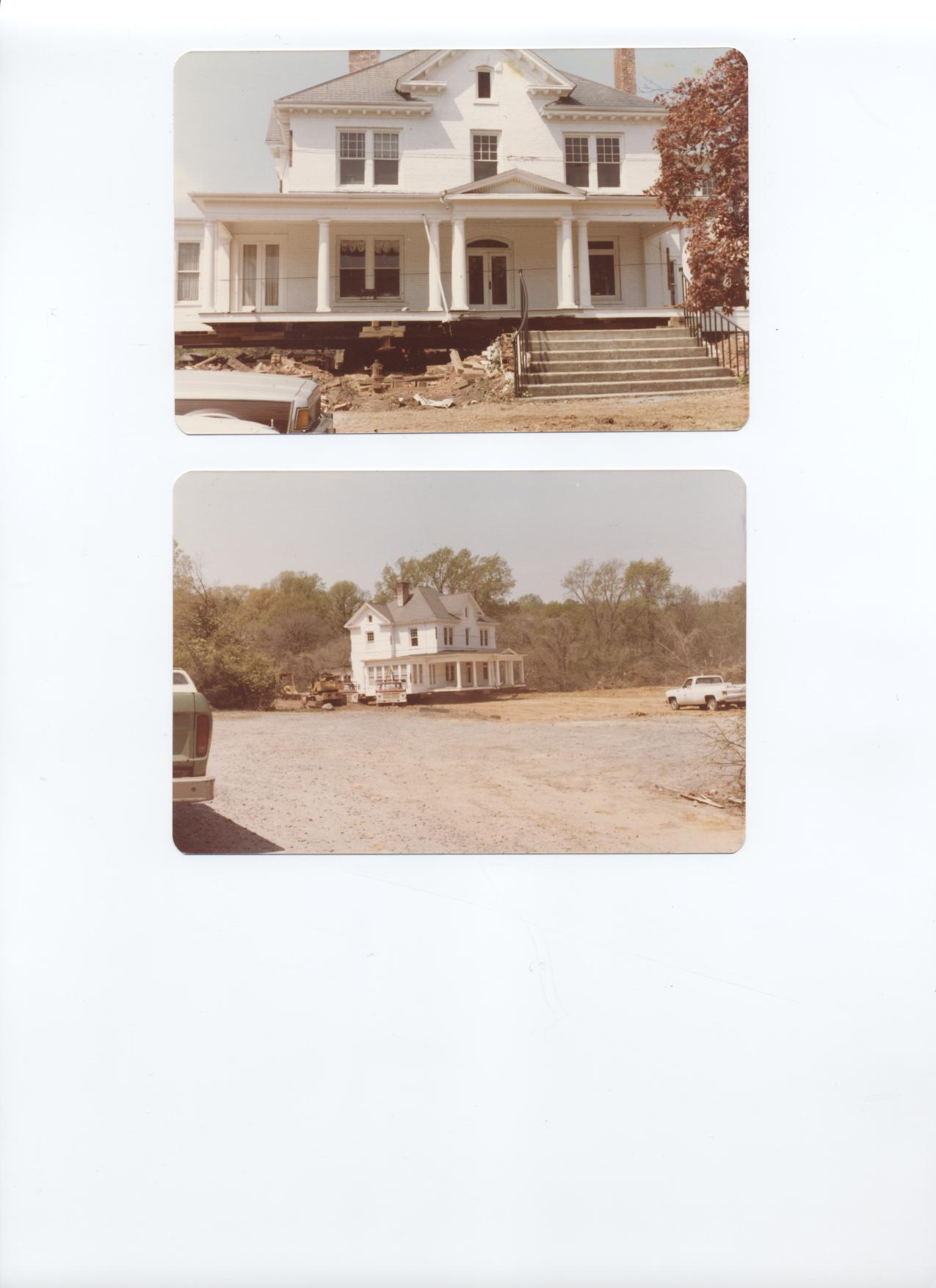

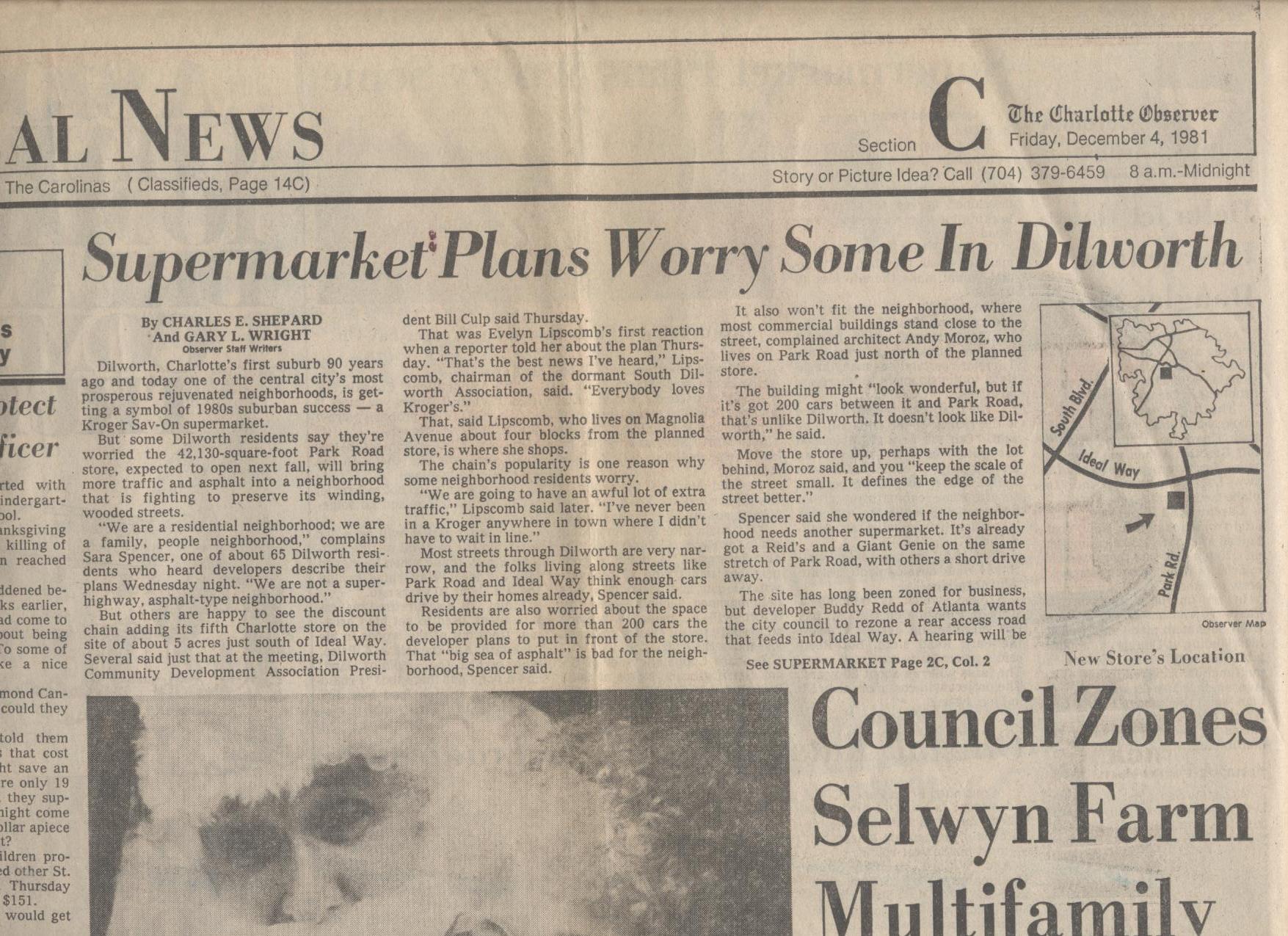

Gallery of Historic Photos and Newspaper Clippings

In in her later years, Sue Parker, a key figure in the story above, visited Dilworth Center with a folder of original photographs and newspaper clippings. She expressed heartfelt gratitude that the house had become a place of hope and healing. The materials were carefully scanned and digitally preserved to honor and protect the legacy the house.

Full Timeline:

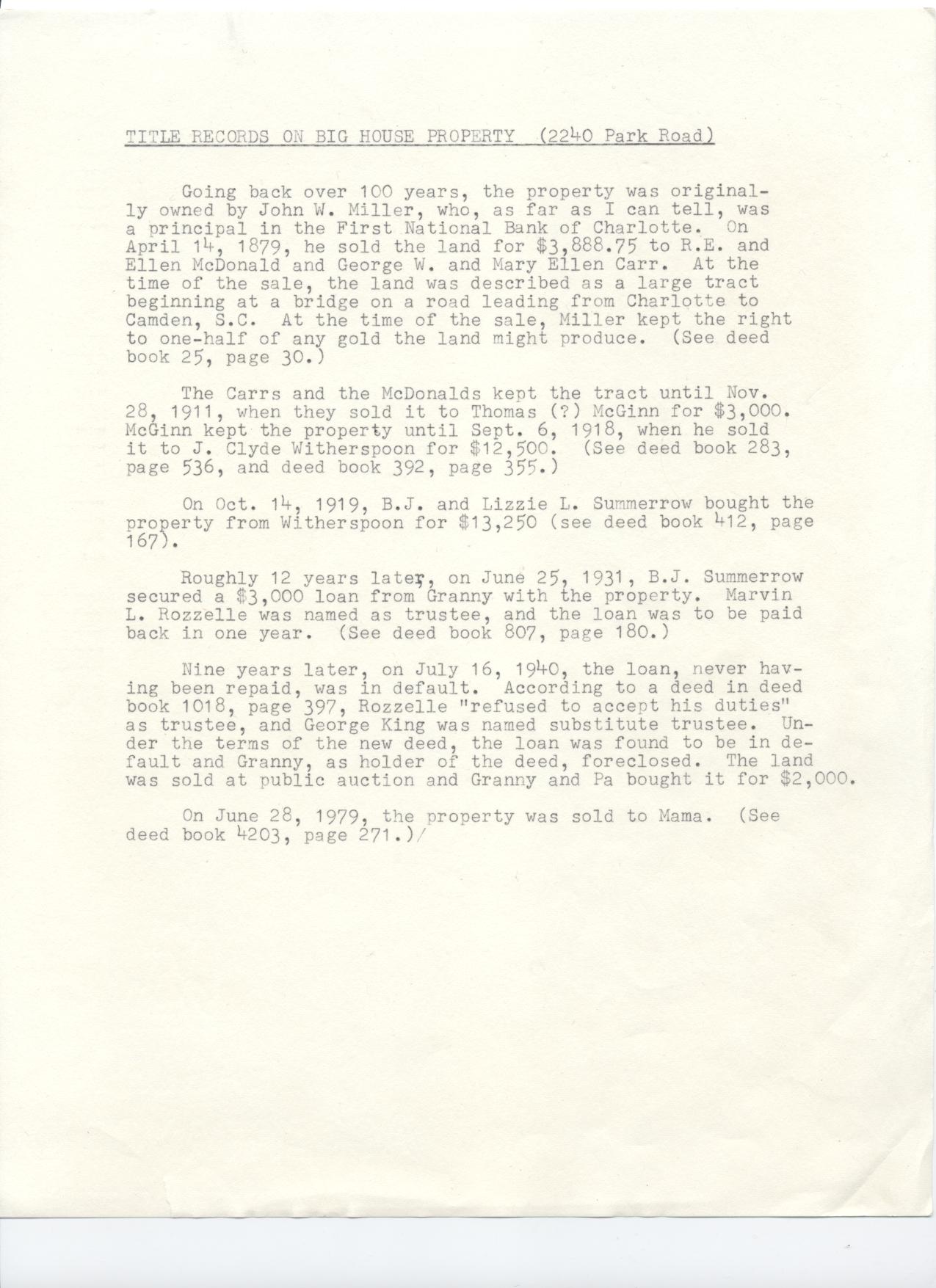

Land History, and The Dilworth Kroger Debate (1879–1984)

1879

April 14, 1879: John W. Miller sells a large tract of land (including what would become 2240 Park Road) for $3,088.75 to R.E. and Ellen McDonald and George W. and Mary Ellen Carr.

Notably, Miller keeps the rights to “one-half of any gold the land might produce,” hinting at historical mining interest in the area.

1911–1919

November 28, 1911: McDonald and Carr heirs sell the land to Thomas McGinn for $3,000.

September 6, 1918: McGinn sells to J. Clyde Witherspoon for $12,500.

October 14, 1919: Witherspoon sells the land to B.J. and Lizzie L. Summerrow for $13,250.

1931–1940

June 25, 1931: B.J. Summerrow secures a $3,000 loan using the house as collateral.

July 16, 1940: The Summerrow family defaults on the loan. The property is foreclosed and bought at public auction by “Granny and Pa” for $2,000.

1979

June 28, 1979: The property is sold to "Mama" (Sue Parker), marking the beginning of the modern controversy when the Parker family becomes involved in development discussions.

1980

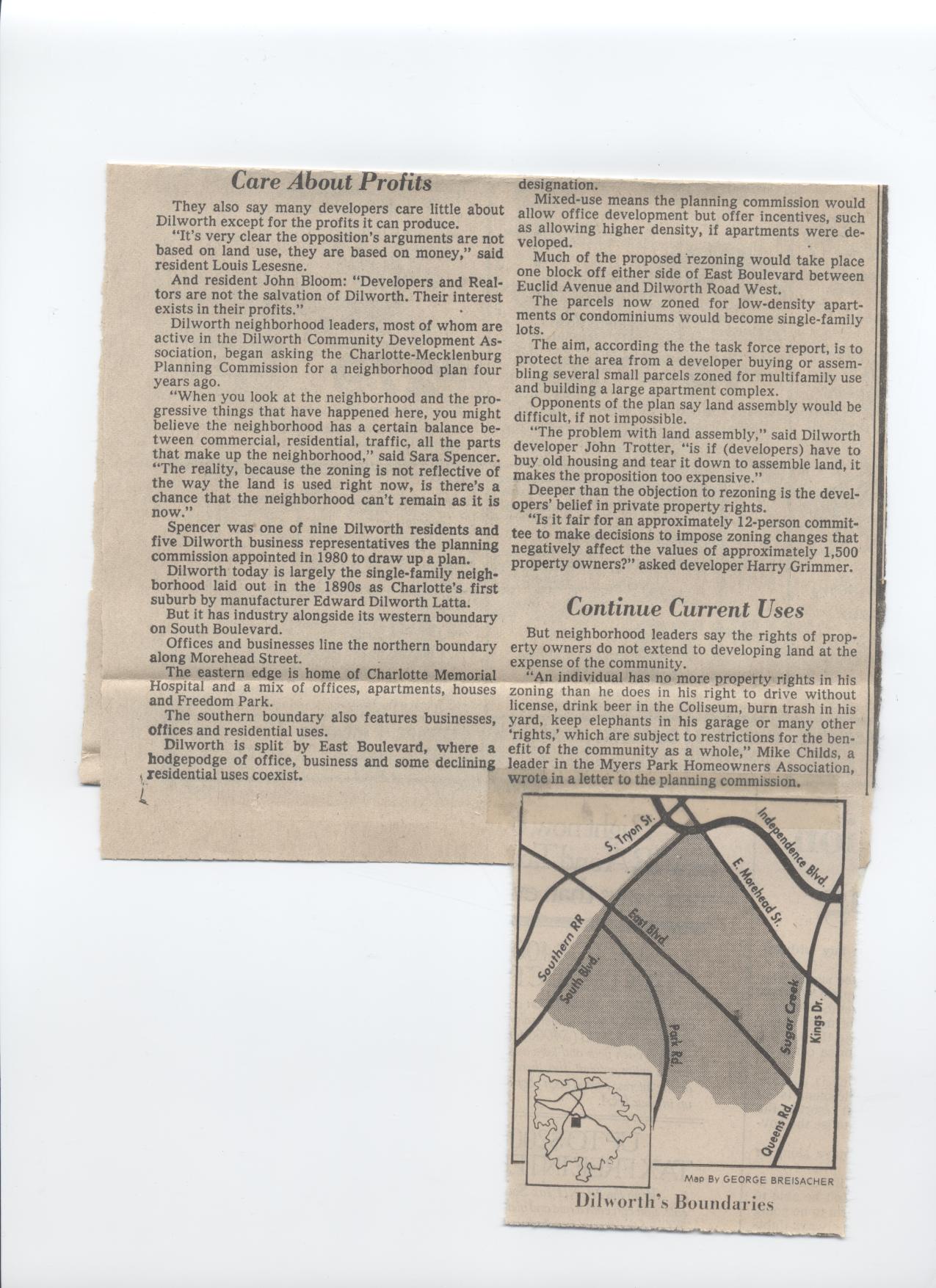

DCDA Mobilizes: The Dilworth Community Development Association (DCDA) begins organizing to request zoning protections and preservation efforts.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Planning Commission appoints a neighborhood task force, including residents and business leaders, to draft the Dilworth Small Area Plan.

1981

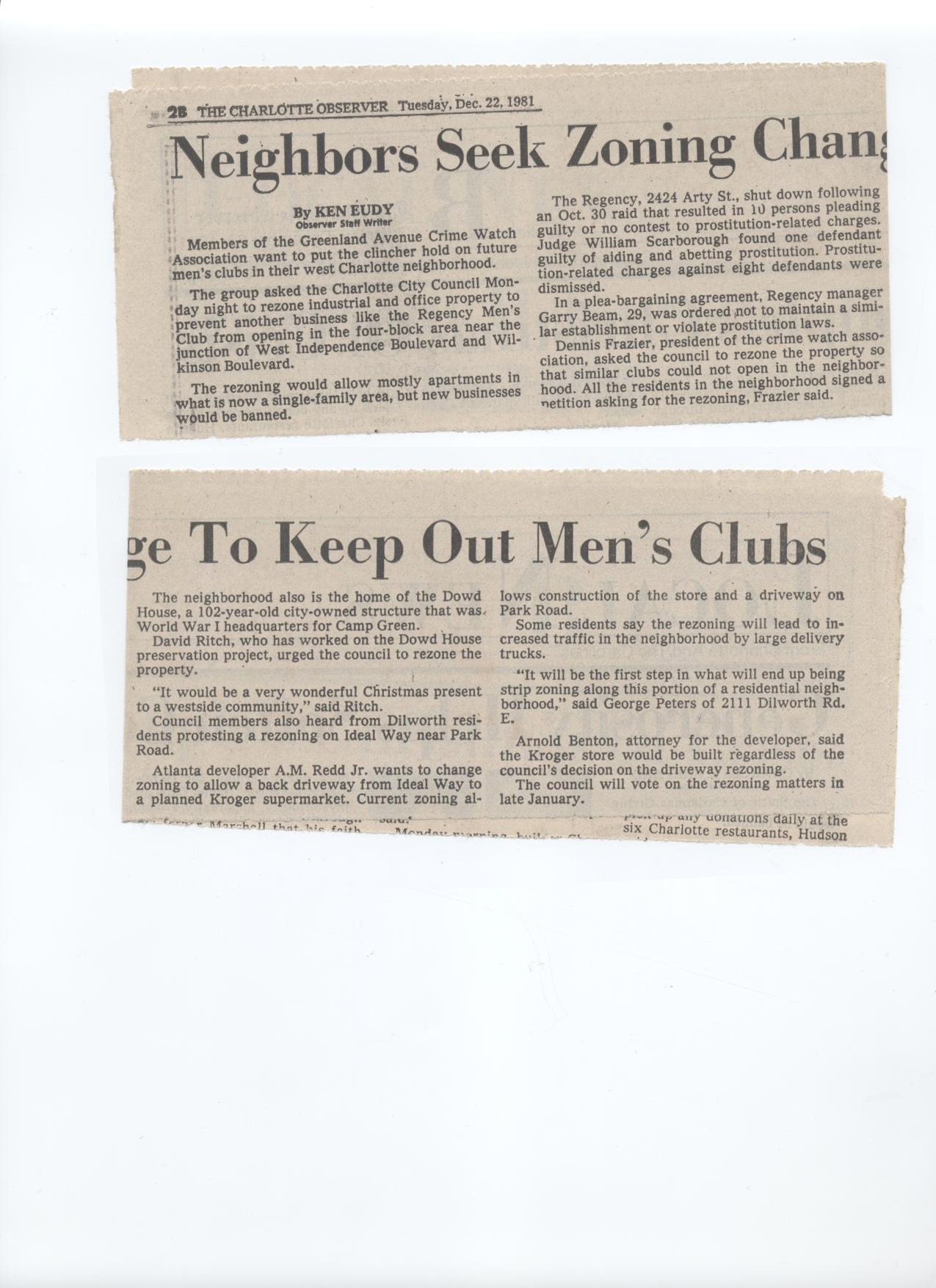

Down-Zoning Discussions: More than 900 parcels in Dilworth are recommended for down-zoning to preserve the character of the neighborhood and discourage large-scale development.

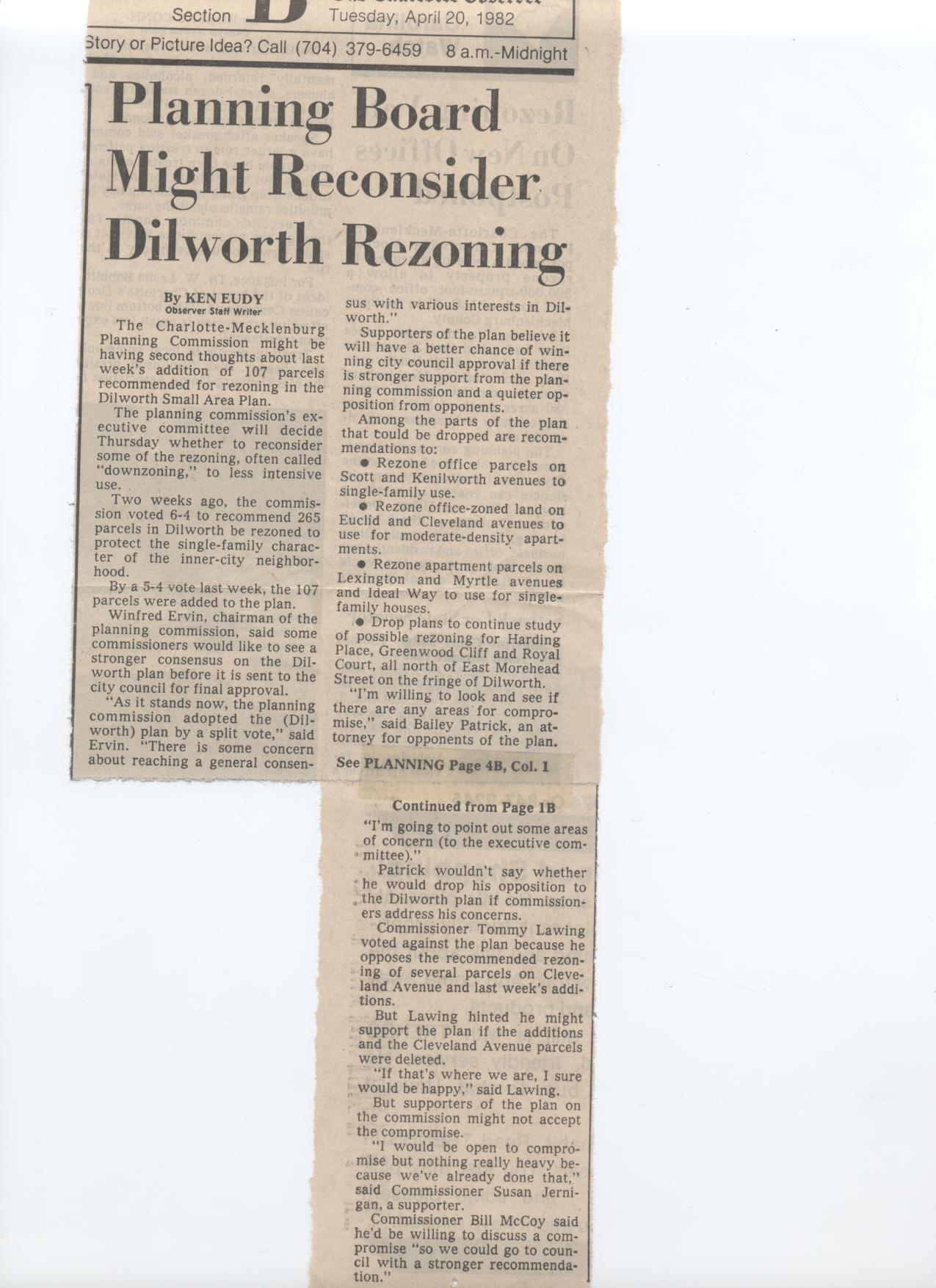

1982

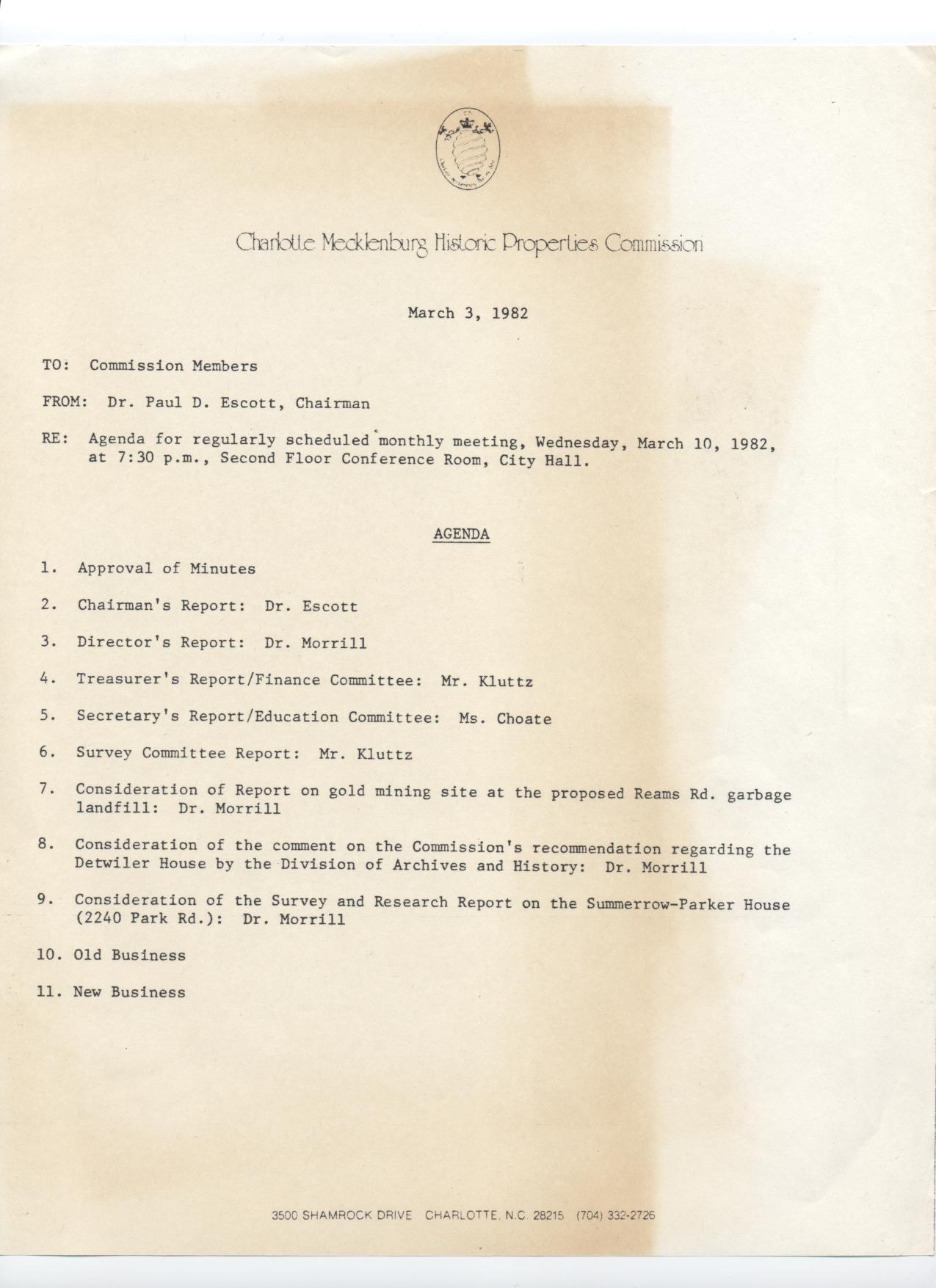

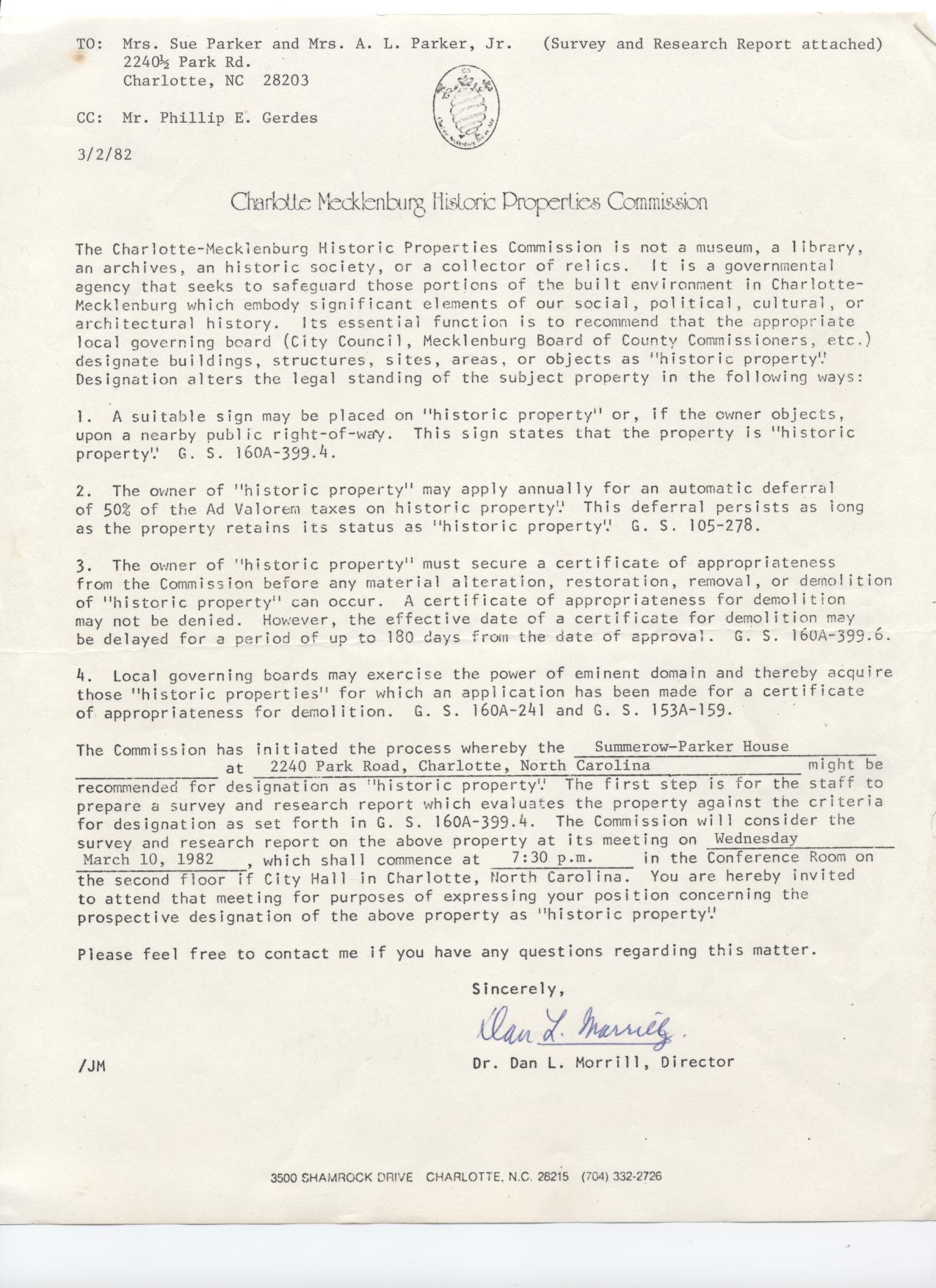

March 2: The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Properties Commission notifies the Parkers of a hearing to designate the Summerrow-Parker House as a historic property.

March 3: The Commission agenda includes consideration of this house alongside the broader historic preservation and gold mining site concerns.

March 10: A formal hearing is held on whether to recommend the Summerrow-Parker House for historic designation.

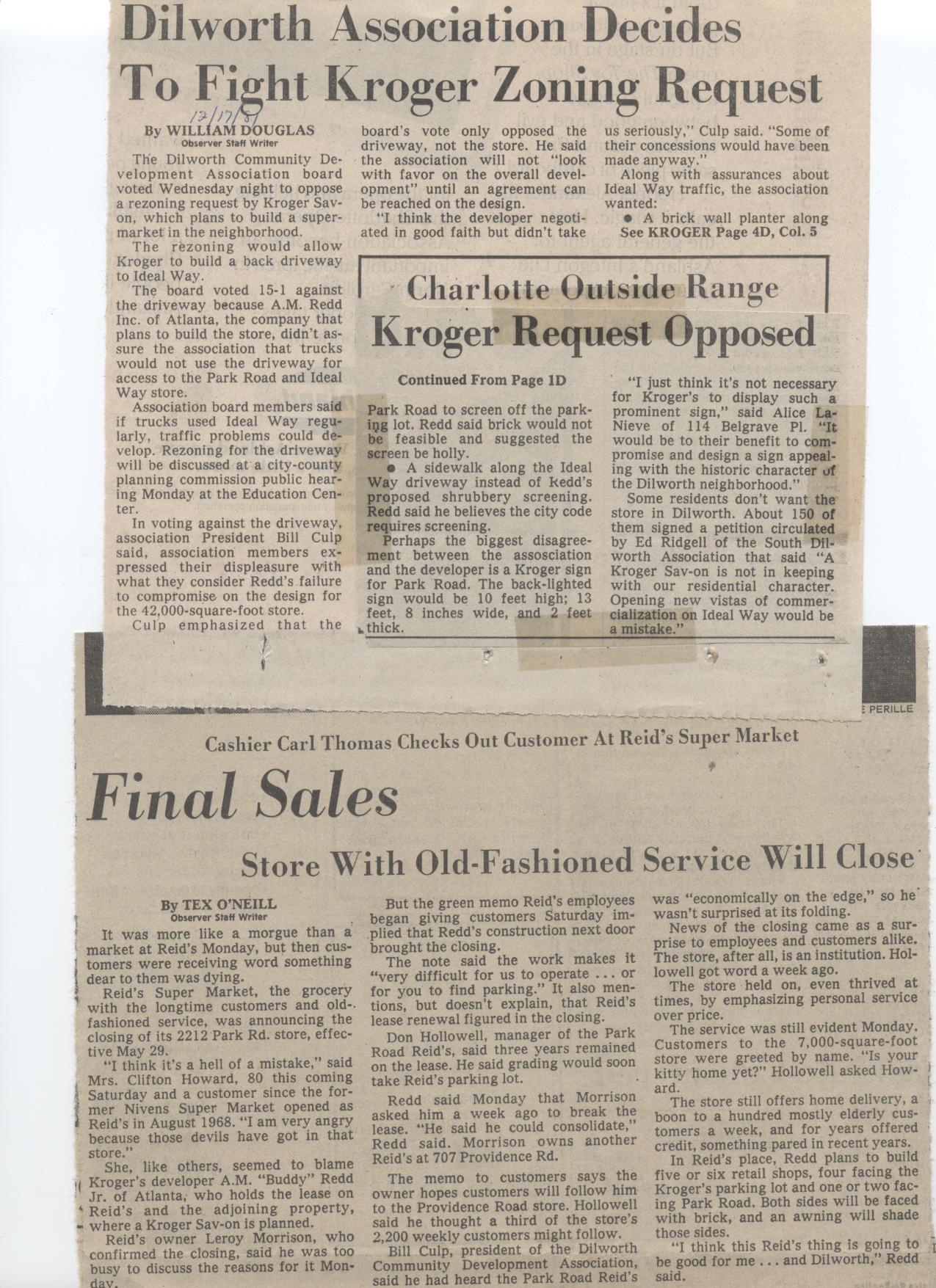

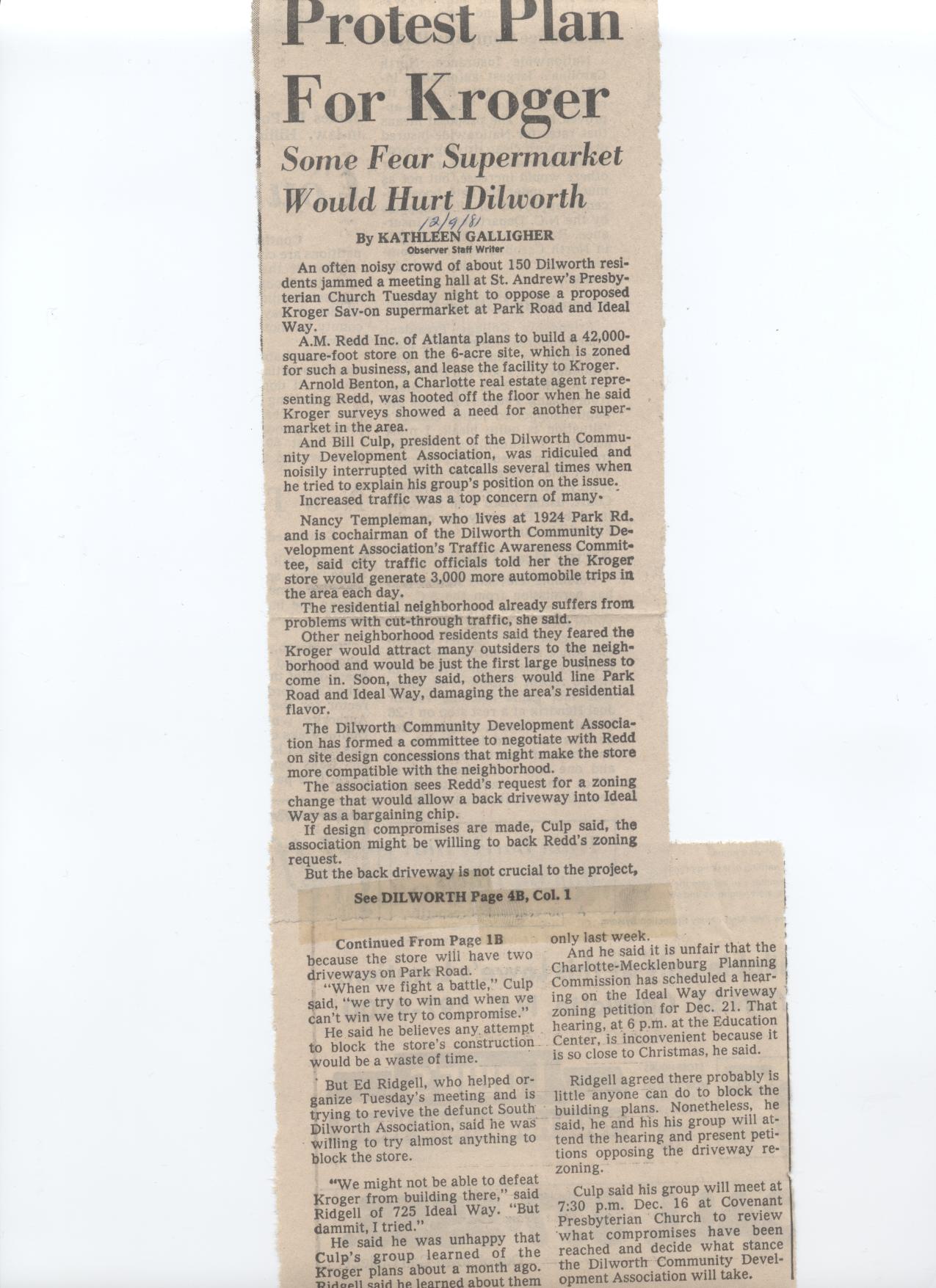

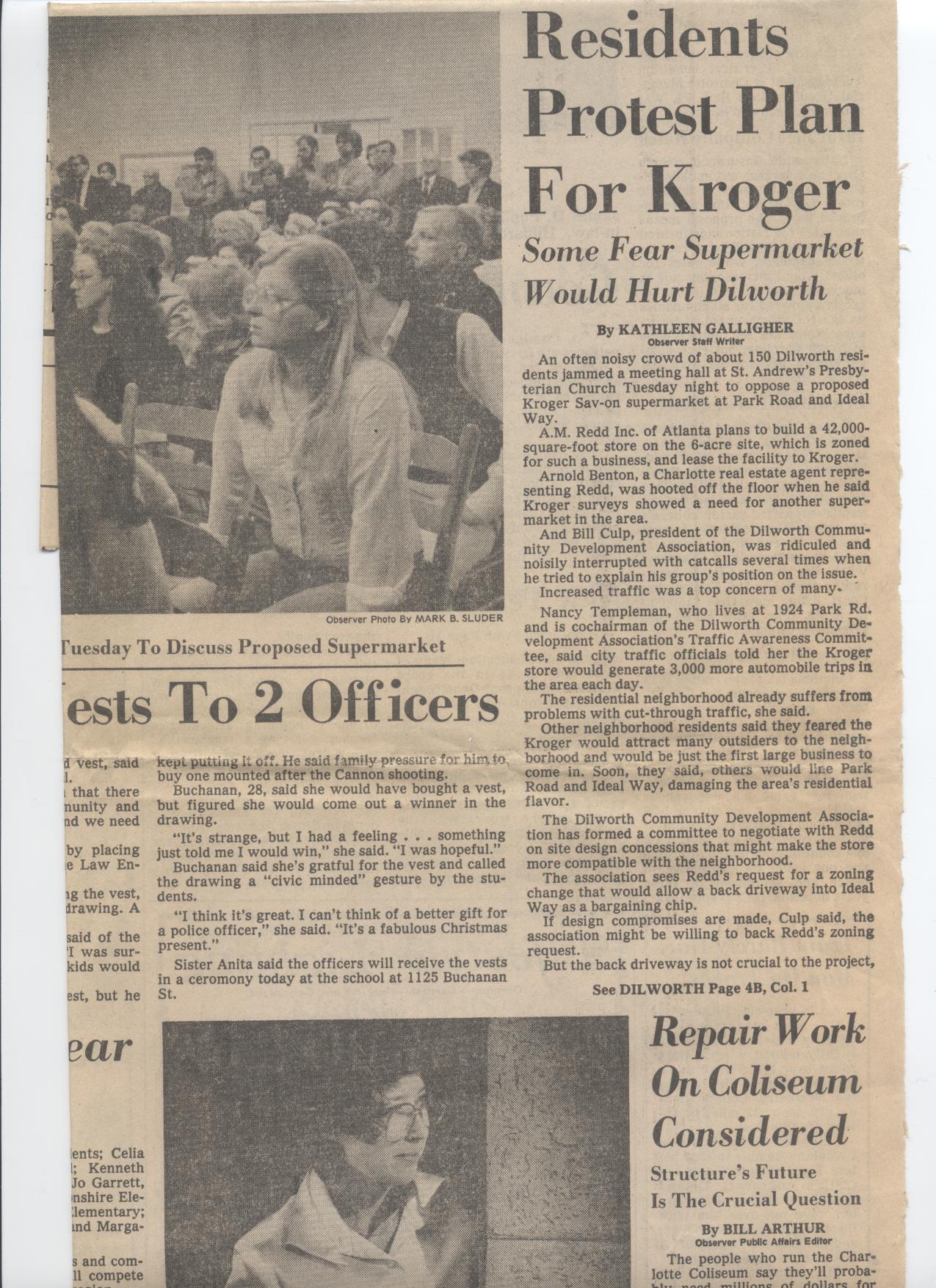

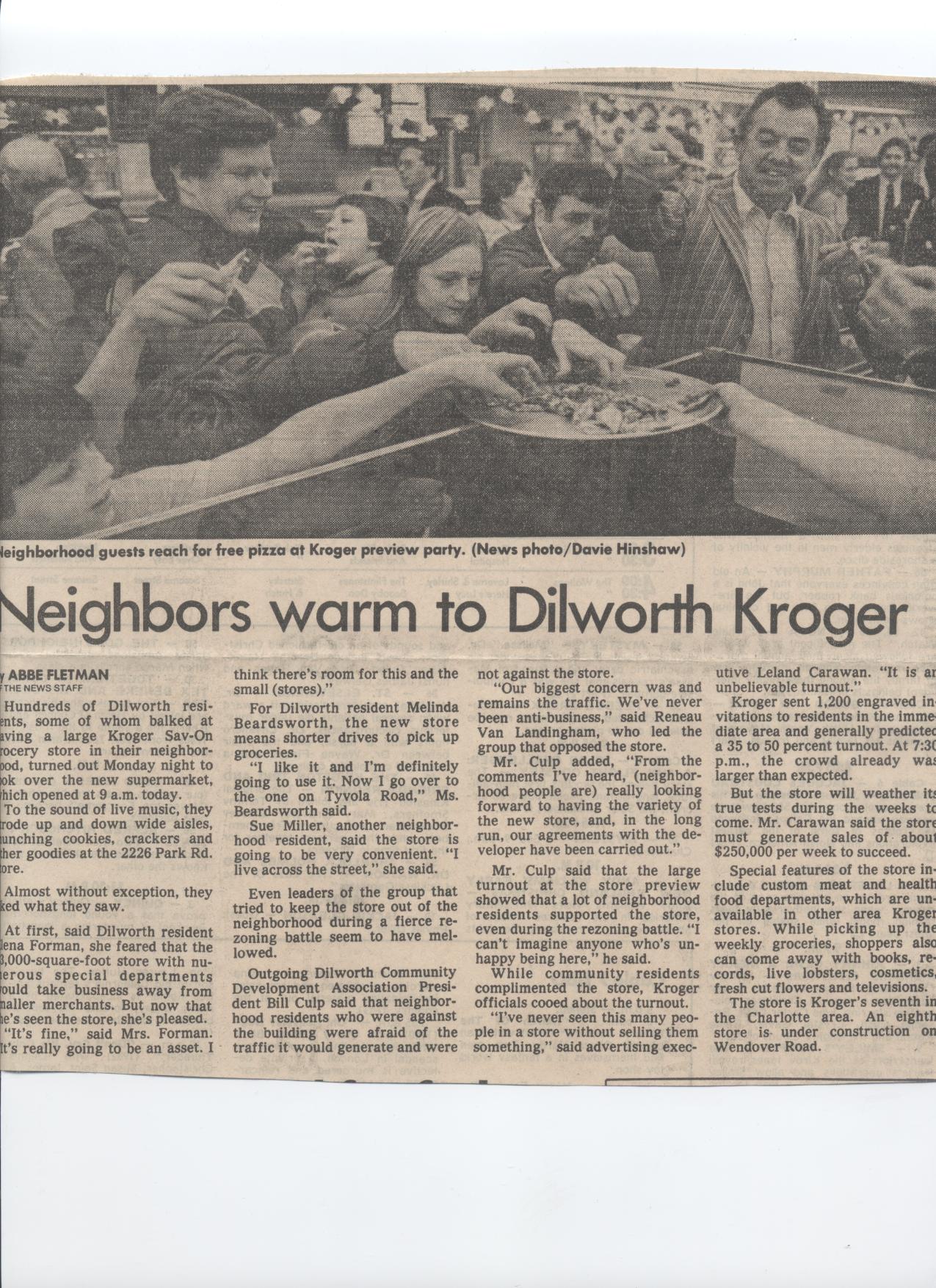

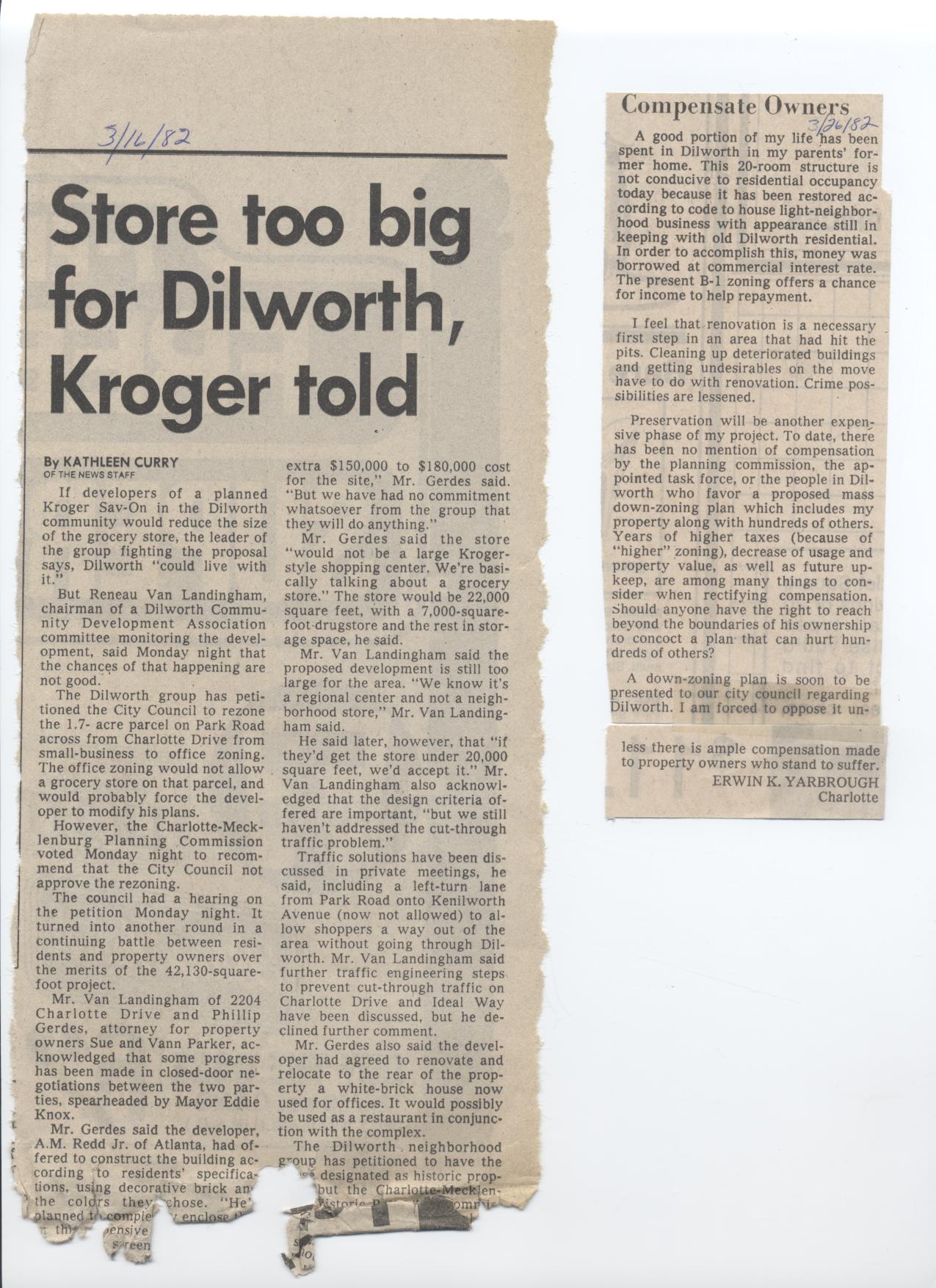

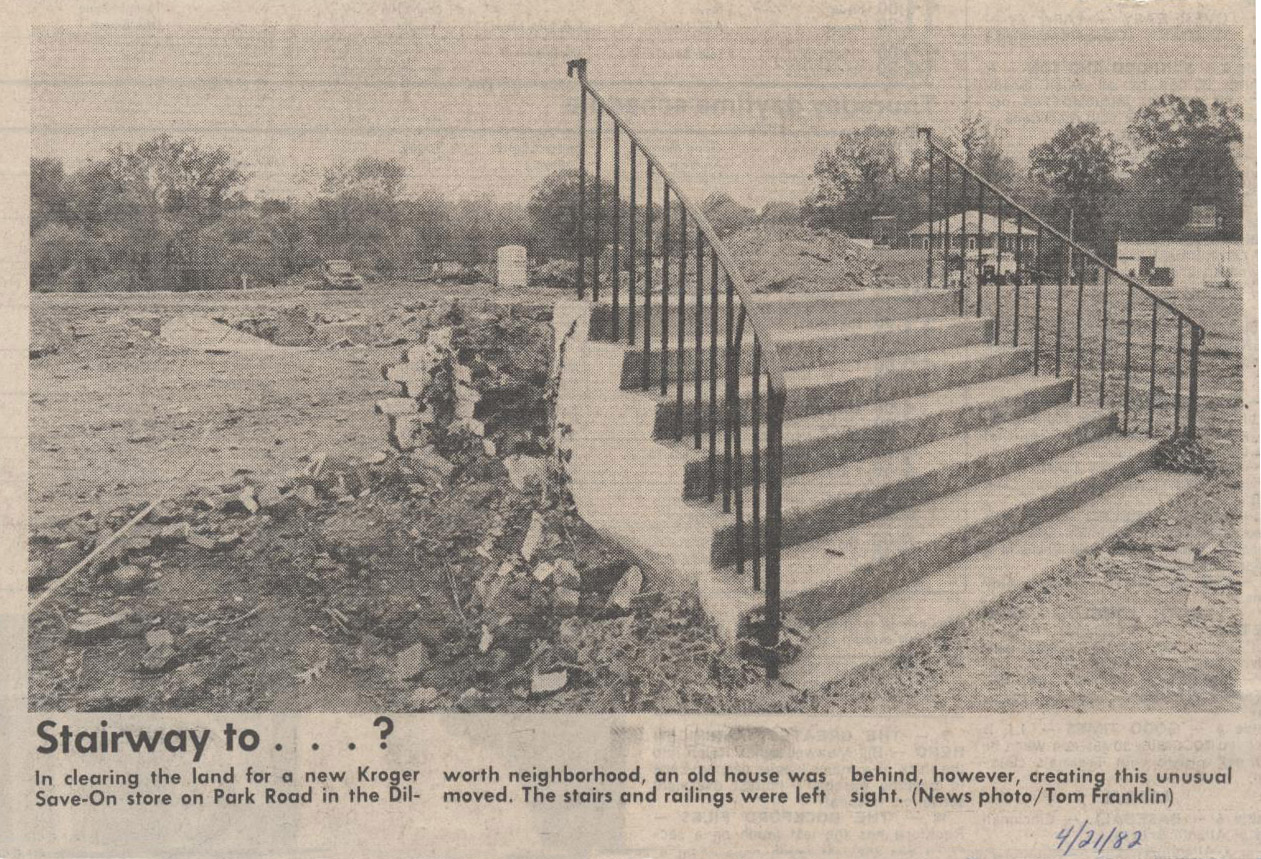

March 16: News breaks that developer A.M. Redd Jr. is proposing a 42,000 sq ft Kroger store at 2226 Park Road. Strong community opposition emerges.

March 23: Charlotte Observer editorial “A Healthy Fight” reflects the divided public opinion and civic energy behind the controversy.

April 1: Editorial “Dilworth’s Deal: Now the City Should Help” encourages the City Council to consider mitigation efforts as the development moves forward.

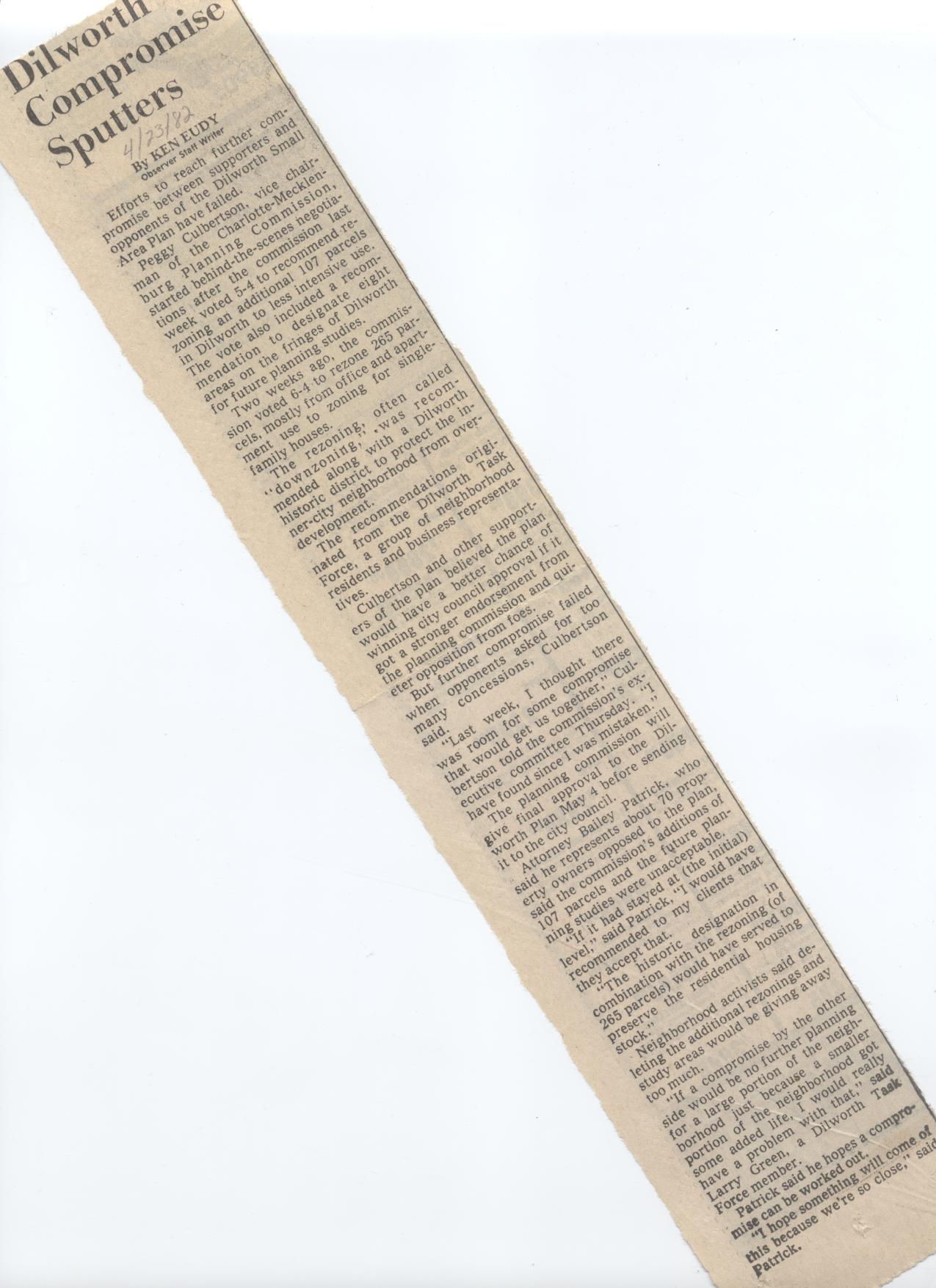

April 6: The Planning Commission discusses zoning proposals and debates involuntary vs. voluntary rezoning procedures.

April 7–8: Residents express concern over “cosmetic” concessions, increased traffic, and harm to local small businesses.

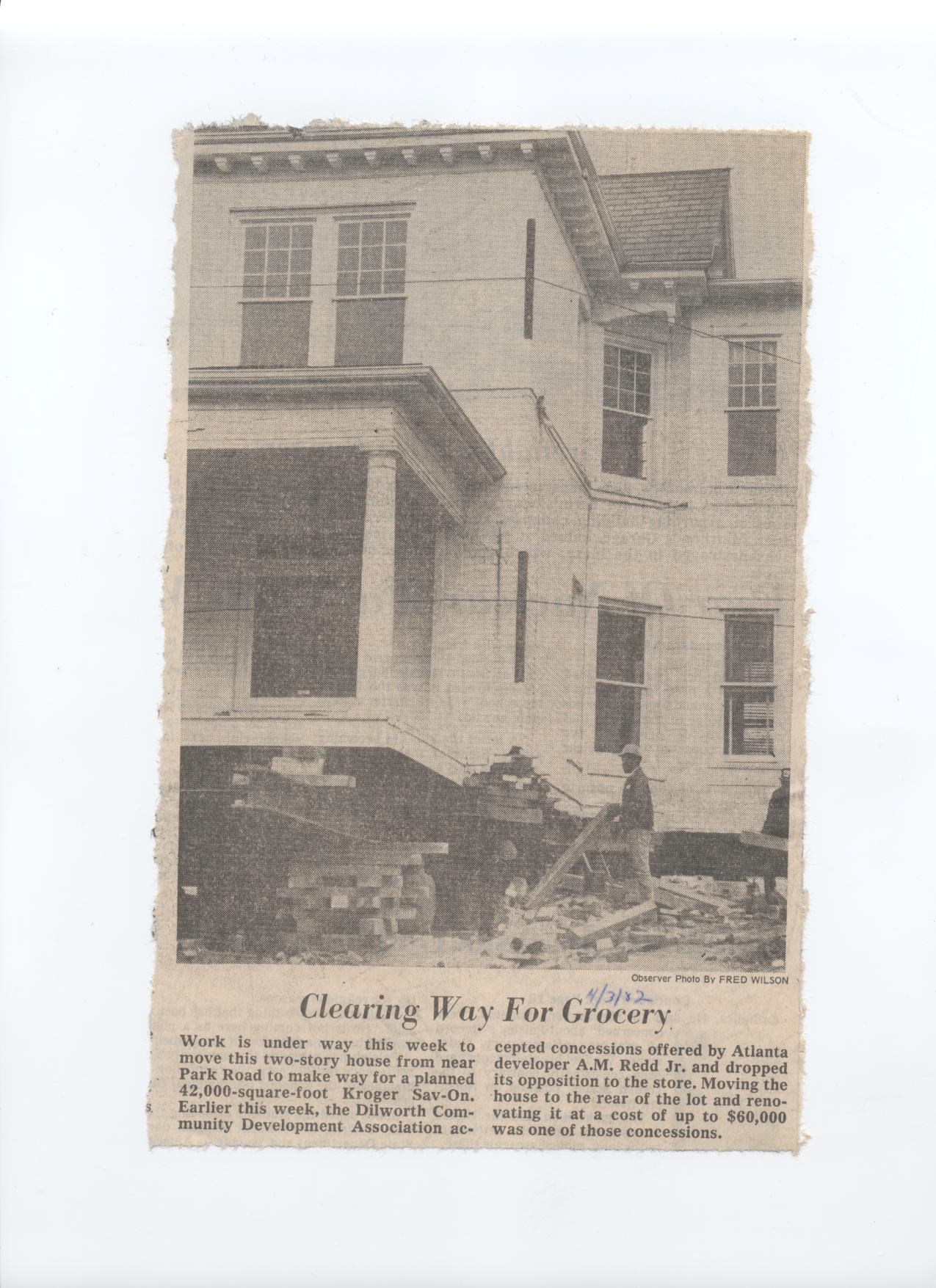

April 13: Work begins to move the Summerrow-Parker House to the rear of the lot. Redd agrees to cover up to $60,000 in costs as part of concessions.

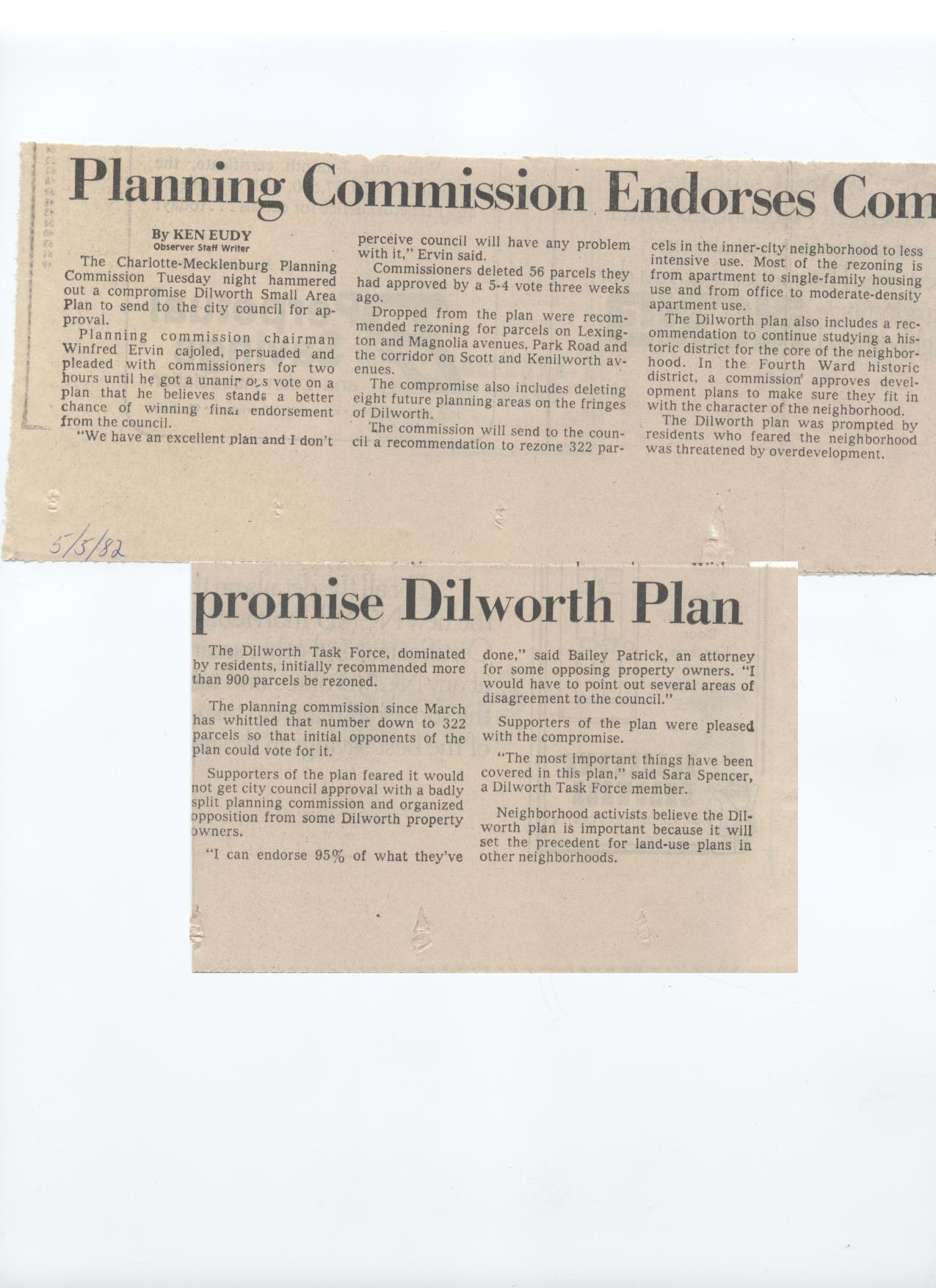

April 14: The Planning Commission votes to reduce the rezoning proposal from 928 to 372 parcels.

May 5: A compromise “Dilworth Plan” is approved by the Planning Commission, balancing historic preservation with development.

1983

January 20: Van Parker (son of the property owner) writes a personal letter defending his mother’s decision to sell the land. He criticizes selective historic preservation efforts and argues that the Kroger project meets zoning requirements.

March 30: The DCDA votes 12–3 to drop formal opposition to the Kroger development in exchange for concessions.

Concessions include:

Brick on all sides of the building

Landscaping buffers

Reduced signage size

Reduced lighting after 10 p.m.

Preservation of the Summerrow-Parker House

May 1983: City Council moves forward with rezoning approval, and the project advances toward completion.

1985

July 9: Developer A.M. Redd seeks further rezoning to add shops behind the now-operational Kroger.

The plan includes converting the relocated Summerrow-Parker House into a retail structure.

James Major Hanson purchases the relocated house and opens J Major’s Total Concept Weddings, a full-service wedding planning business, on the first floor.

The second floor is leased to a variety of tenants, including a hair salon, counselor, and photography studio.

1992

Tammy Furr, then a student at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, begins working at the wedding shop, where she meets her future husband Mark Hanson, James’s son.

2001

Tammy Hanson (formerly Tammy Furr) earns her master’s degree in social work and begins an internship with Dilworth Center, then located at 429 East Boulevard.

2005

Dilworth Center is forced to find a new location when its current property (429 East Boulevard) is listed for sale.

At the same time, a deal to sell the Summerrow-Parker House by James Hanson to local land developer falls through.

Tammy connects the Dilworth Center CEO and board members with her father-in-law, James Hanson. A capital campaign is launched to buy the building.

September 2005: Dilworth Center purchases the historic home and renovates it for drug and alcohol treatment use.

2014

A 4,000-square-foot addition is constructed to expand services.

The renovation preserves the building’s historic character using reclaimed bricks from a former Schwinn bicycle factory.

2025

Dilworth Center celebrates 35 years of operation.

The house stands not only as a symbol of neighborhood preservation but also as a beacon of recovery and service to the Charlotte community.

* Fun Fact: Tammy Hanson now serves as Dilworth Center's Chief Operating Officer, with 24 years of service to the organization.